Death: Isaiah 2:1-5

were we led all this way for

Birth or Death?

Words from the nameless wiseman towards the end of T.S. Eliot’s great poem The Journey of the Magi are a strange place to begin an Advent sermon you might think. Strange because it takes us straight to the end of the journey we will walk this Advent. After all, surely the one thing everyone knows about this time of year is that there will be a birth.

But what Eliot’s words remind us is that the Christian journey to the crib, the journey we share with the Magi is not an easy one. The cost of Christmas is that, as we journey towards the crib, we know that it also leads to the cross. That that birth leads to that death. So as we recognise the hardness of this journey we also recognise that this is indeed a fitting place to begin our Advent journey.

For centuries, the Church used Advent to reflect not simply on the promise of a birth, but to spend this time reflecting on our own mortality, our own fragility and limitations. This has traditionally been done through and examination of "The Four Last Things": Death, Judgement, Heaven, and Hell.

This reflection on our limitations, and our total reliance on the gift of that promised birth, is why this is a penitential season. Like Lent we put aside Glorias and Alleluias, and don purple as we reflect on our own shortcomings as we ask again whether we “were will led all that way for Birth or Death”.

These reflections are an opportunity to explore in turn The Four Last Things. Using readings from the book Isaiah I hope they will be an opportunity for us to reflect on this great Christian tradition, and through that understand again the transforming promise God makes to us in Advent.

The book of Isaiah is a fitting companion for our journey because of the vital role Isaiah plays in our understanding of the promise of Christmas.

Often described as ‘The Fifth Gospel’, the book of Isaiah contains within it many of the great prophesies of the Messiah quoted in the Gospels: the Virgin Birth, the Son of David. More than that it also carries with it the imagery and poetry we have subsumed into our imaginative telling of the Christmas story. Try as you might, you can't find ox and ass lowing in the Gospels; but they are there in Isaiah.

So as we begin to reflect on ‘Death’ – the first of our four last things – it is right that we begin at the start of the greatest of the prophetic books of the Old Testament.

Death is a hard place to start. It is a hard place to start because death seems so final. Even if we live in “sure and certain hope of the resurrection to eternal life” there is still a finality, an honest certainty to death. Much of this is just a fact of life. There is after all nothing certain in life except death and taxes. In our modern world death has become a singular state defined solely as the opposite of life.

But in the world of Isaiah, in fact in the world before our modern scientific age, death had a fuller meaning. Of course, death was that state which existed after the end of life. But death was also a state which surrounded us in life.

“In the midst of life we are in death”, we hear in the Book of Common Prayer. Words drawn themselves from the mediaeval funeral rites. Death in this pre-modern sense is less a scientific fact, and more a living-state where life cannot be lived. Whether through violence, or chronic illness, or the sheer fact of frequent and seemingly random mortality; death was a part of pre-modern life in a way which is hidden from the vast majority of us.

But we kid ourselves if we think that there are not those in our world who live in the midst of death. Countless numbers live in the midst of the death of grief, or chronic illness, the living-death of war or abuse. But I want to focus on one experience of this modern living-death, hidden in plain sight, the living-death created by the crippling power of debt.

In case you missed it, the last Friday in November was “Black Friday”. If you weren’t up at 5am spending-spending-spending then by all modern measures you were clearly doing something wrong. Over £2 billion spent on "Black Friday". Some of that spending was no doubt for Christmas presents and gifts for loved ones. But much of it will have been spending for spending’s sake. And many people can’t afford this.

We live in a country where the average household now has £10,000 of non-mortgage debt. Finance through credit-cards and pay day lenders is easily available. Lives are ruined by debts which snowball, and lives entrapped by the clutches of loan sharks. This time of year as we are surrounded by adverts which tell us to “buy this” and “buy that”, to “just have one more”, and then another, and then another, and then well, you might be happy, for a moment.

But life doesn’t work like that. Money is a great servant but a terrible master. To live in debt, to live with money as your master is to live in a state a state of living-death. Not knowing how bills will be paid, how the house will be heated, how food will be bought.

In the midst of life we are in death.

But it does not have to be this way.

In Isaiah we hear God’s promise to the power of death – all death – with his promise of life. The prophet tells us:

He shall judge between the nations,

and shall arbitrate for many peoples;

they shall beat their swords into ploughshares,

and their spears into pruning-hooks;

nation shall not lift up sword against nation,

neither shall they learn war any more.

This is such a well known passage that it is worth spending a little time with it.

The remarkable power of this promise is not that peace will come – that is after all the promise that all political leaders offer - but that peace will come peaceably.

God’s promise is not to fight the forces of death and destruction with more death and destruction. But that life shall over come death as ‘nation shall not lift up sword again nation/ neither shall they learn war any more.’

This powerful promise of the victory of peace, or the defeat of violence and death is made more transformative because this is achieved not by the casting down of the implements of death, but by their transformation.

they shall beat their swords into ploughshares,

and their spears into pruning-hooks;

These words can guide us all as we search for life in those forms of living-death we find in our contemporary society.

We naturally focus on the military aspects of this passage – but there is also a deep economic message it tells. Swords and spears – like our modern weapons of war – were very expensive in the time if Isaiah. So, to say that they should be transformed into tools for growing food was not just a poetic argument, it was an image of how we can transform the relationships of death through the wise and generous use of wealth and money.

Recently the Lifesavers project was launched. A Church of England initiative to teach young people the value of sound financial management so that we nurture a generation aware of the dangers and pitfalls, aware of the living-death, that poor financial management can create. Here in this project we have our own modern version of swords being turned into ploughshares and spears into pruning hooks.

Through Advent we ask again whether we will journey all this way for a birth or a death. As with the Magi of Eliot’s poem we come to recognise that rather than opposites, the two are inseparable. That we can only find the true meaning of God’s promise if we face up to living realities of death.

But on this Advent journey we find again in that birth that deep promise that Isaiah speaks of; that contained in this promised birth is God’s deep promise to overcome all death.

Judgement: Isaiah 11:1-10

Like all great novels Carr’s masterpiece conjures with a series of overlapping themes.

There is the trauma and healing of the years following the First World War where Birkin served as an advanced signalman in the trenches. This mirrors the ongoing cost of the Great War on the people of the fictional Yorkshire village of Oxgodby where Birkin finds himself.

There is the theme of sanctuary where Birkin, hiding from the break-down of his married life in London, seeks the solitude and safety of this idyllic setting.

But behind these overlapping themes comes the theme of judgement.

Through the pages of this book judgement is writ large in the form of Birkin’s employment. An art restorer, Birkin’s task through the novel is to uncover and restore a medieval ‘Doom’ painting on the wall of the small church in Oxgodby.

As the novel begins this theme of judgement is present in everything Birkin does. As he painstakingly begins to uncover this great image of Christ sitting in Majesty we hear those great mediaeval pronouncements of judgement:

And he shal com with woundes rede

To deme the quikke and the dede…

And as he reveals this tableau of judgement we hear Birkin’s own judgement on the people that he encounters. Birkin, a Londoner, initially struggles with Yorkshire, which he sees as “enemy country”. He is dismissive of his employer: “Much can be said against the Rev’d J.G. Keach" Birkin says, “But when he stands at the Judgement Seat, this also must be said in extenuation – he was business like.” Sleeping in the Belfry of the church to save money he pours judgement on all he has met:

"‘And what about poor Birkin, did any of you offer him bed and board?’ Yes, you blasted smug Yorkshire lot, what about Tom Birkin – nerves shot to pieces, wife gone, dead broke? Yes what about me?"

In Oxgodby Birkin finds himself literally and figuratively standing in a place of judgement where his initial brittle judgements mirror the judgement of the slowly uncovered wall painting.

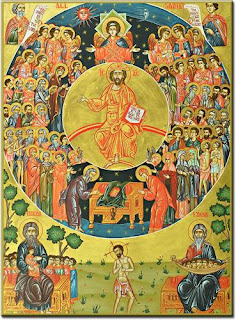

This form of judgement, writ large in these great Doom paintings, looks ahead to the end of time and the chief activity of Christ. Through them we see an image of God’s Judgement which is sudden, terrifying, and certain. Often painted on the Chancel arch of a Church to remind all in the congregation of the Judgement that lay ahead of them. As Tom Birkin describes the Oxgodby Doom.

[The uncompromising] Christ in Majesty at its apex, the falling curves [of the arch] nicely separating the smug souls of the Righteous trooping off-stage north to Paradise, from the Damned dropping (normally head first) into the bonfires.

It is easy for us to dismiss these Doom paintings as a relic of a bygone era, but they should remind us of the deep question of faith we too often skate over; what will come of us when we stand in the place of Judgement?

It is an inescapable fact of scripture that judgement stands before all of us. In this Advent season, and as we consider the Four Last Things, we come to that theme of judgement.

It would be nice to think that judgement is one of those red-blooded Old Testament themes that Jesus helpfully softens for us. But as we see in John the Baptist’s prophesy, Christ comes in judgement:

His winnowing-fork is in his hand, and he will clear his threshing-floor and will gather his wheat into the granary; but the chaff he will burn with unquenchable fire.

Judgement is inescapable in scripture.

However too often the Church has been flat-footed as it speaks of judgement. Judgement, the Church has too often said with a certainty beyond its pay grade, is definitely for those with different backgrounds, different orientations, different beliefs who have the unhappy misfortune to be unlike us.

In this way the judgement of the Church has existed as a projection of the prejudices carried by the one doing the judging. So, the uncompromising Christ in majesty of the Doom paintings tells us about the concerns of the mediaeval mind.

Equally Birkin’s initial judgement of the people of Oxgodby tells us about the anger and grief he carried with him to that idyllic place that summer in the 1920s.

The limit of these approaches is that judgement, if we speak of it at all, is seen solely as an aspect of God’s future activity.

But there is another way to think of judgement.

In our reading from Isaiah we find that judgement still lies ahead of us, but it exists as the consummation, the final act, of the transformation God promises to all creation here and now.

In our reading from Isaiah we hear vividly of the promise of this transformation which is grafted from the deep roots of God’s deep promise to his people.

A shoot shall come out from the stock of Jesse,

and a branch shall grow out of his roots.

The judgement that will come is then drawn from this same root. It will not be one of an Apocalyptic Santa seeing whether we have been good and bad. The promised judgement of God will be a reflection of God’s true nature revealed through his ongoing promise for his creation.

God’s judgement is not a future action, but an outflowing of this vision of justice and peace where the most vulnerable are treated with the same dignity as the strong; where all can live without fear.

The wolf shall live with the lamb,

the leopard shall lie down with the kid,

the calf and the lion and the fatling together,

And out of this vision emerges the one who judges from the heart of this promise: “a little child shall lead them” Isaiah says.

As Carr’s novel develops so does the theme of judgement.

As the story continues we find that Birkin changes. So, his gruff and uncouth Yorkshire brethren change from an enemy to become a symbol of a gentler and more innocent time he fears will be lost in the march of modernity. The Churchgoers he ridicules at the beginning show him generosity and hospitality, mostly through the life of the Methodist Chapel, drawing him into the innocent joys of their collective life. Even his view of the Rev’d J.G. Keach is softened, if not overcome, through his growing fascination and infatuation with Keach’s young wife Alice.

Through his time in Oxgodby Birkin is transformed. Birkin, who is standing in his place of judgement is transformed through his experience of that place of judgement.

Carr’s novel is not a quasi-religious text, and is in many ways powerfully critical of organised religion. But it does act as an allegory through which we can reflect on the theme of judgement this Advent.

In Advent we stand, as Birkin does, in a place of judgement. But this judgement is not a distant future act, it is as Isaiah reminds us, the final outworking of God’s transforming promise to creation here and now.

As we consider this promised judgement, as we think on this Last Thing, God does not invite us to consider where we might place ourselves stand on the chancel arch of judgement. God invites us to remake ourselves in the light and love of his transforming promise; to be led by that little child who will, at the end of all things, judge both the quick and the dead.

Heaven: Isaiah 35:1-10

Of all the Four Last Things – Death, Judgement, Heaven, and Hell – I would wager that heaven is the one that we find the most approachable. The pages of scripture, as with the images and language of art and popular culture, are full of predictions and perceptions of what heaven might look like.

For me one of the most powerful of these comes in Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s 1946 film A Matter of Life and Death. The film, if you don’t know it, begins with Peter, played by David Niven, piloting his stricken Lancaster bomber surrounded by the bodies of his dead crew mates. Comforted by the words of an American ground controller named June, Peter prepares himself for what he believes will be his inevitable death. However, an administrative error by the authorities in heaven means that Peter is not collected by Heavenly Conductor 71 and so cheats death, waking on a beach of southern England. There he meets and falls in love with June.

Confronted by this angelic clerical error Peter refuses to leave and so a heavenly tribunal is called to assess his case. This tribunal is grounded in reality by the brain operation Peter undergoes as a result of his injuries. The drama then plays out with the heavenly court – filmed in black and white – cross cutting with the drama of Peter’s operation filmed in colour.

A Matter of Life and Death is a visually stunning film which presents us with an arresting image of the hereafter. The opening sequence counterpoints Peter’s vain attempt to steer his damaged bomber with the steady arrival of his comrades into the arrival lounge heaven. This has added power as this arrival lounge is full of a stream of young people of all races arriving in the uniforms of the Second World War.

However the most visually arresting image of the film is the great moving staircase where Peter, and his heavenly contact Controller 71, play out the pros and cons of his case as he hovers, on this stairway to heaven, between life and death.

Of course this is only a film and so does not present us with an authoritative vision of what God promises to us on the other side of time. But within it is the kernel of that promise we find in scripture, that God’s promises us a home where the limitations and confines of this realm pass away.

This image of heaven as a place without limitation is important as we consider the Four Last Things. We are, in essence, in the Four Last Things considering our own limitations. The limitations of our life and death, the limitations of our actions and judgement. If many of these are perhaps drawn in an exacting light, then in heaven we come to consider these limitations in a more pastoral manner. When we consider the promise of life after death it is natural that this is drawn in contrast to the limitations of this life. So heaven becomes, above all, a place where our earthly limitations are put aside.

In the prayers and liturgies for funerals we constantly circle around this contrast and language, in one prayer invoking the hope of an existence beyond earthly limitations, where ‘all pain and suffering is ended, and death itself is conquered.’

In our reading today from the prophesies of Isaiah we find this great image of an existence beyond limitation played out in poetic terms.

Then the eyes of the blind shall be opened,

and the ears of the deaf unstopped;

then the lame shall leap like a deer,

and the tongue of the speechless sing for joy.

For waters shall break forth in the wilderness,

and streams in the desert;

This vision of a future released from limitations is at the heart of the prophesies of Isaiah. In this complex book the promise of release returns again and again. This promise of release fills the prophetic utterances and poems, written over centuries, which come together in the book of Isaiah. What binds them together is their response to the historic trauma of the Babylonian exile.

The structure of the book of Isaiah then reflects this developing response to the trauma of the exile. Not written by one author, the book moves through a series of related parts which deepen our understanding of God's promise to his people. The first part – First Isaiah – works through the deep grief of the exile and the destruction of Jerusalem. The second part - Second Isaiah - reconciled to this grief, explores the deeper hope that God might offer to his chosen people. At its heart is a deep yearning to return from exile, but this is mirrored with a deeper hope that this salvation will be completed on a cosmic scale beyond the end of time.

Like in Powell and Pressburger’s film this promise lies at the end of a pathway, but instead of being a great moving stairway moving towards heaven it is highway drawing the exiled people of Israel through the desert to their final destination.

A highway shall be there,

and it shall be called the Holy Way;

[…]

And the ransomed of the Lord shall return,

and come to Zion with singing;

This highway has a double meaning. Like the moving stairway, we can read this highway as a route to the salvation God offers us on the other side of time. But, unlike Powell and Pressburger's stairway to heaven, this highway also carried a message for us here and now. Promising, as it did, to lead the exiled people of Israel back from Babylon to rebuild Jerusalem.

The hidden tragedy of this vision is that it is so powerful, so ecstatic, that cannot believe that it could be part of our experience here and now. And so, we push it beyond our earthly experience into a future possibility on the other side of time. And we give that promise a name, heaven.

But in Advent we wait and watch for a promise which is not pushed far off into the future, but a promise which will burst into our present experience. It is a promise which draws us onto that highway, and towards that transformation God seeks for us not far off into the future, but beginning here and now.

In the climax of A Matter of Life of Death we are given a glimpse of the true form of that promise we seek this season. In the final moments of the film the two narratives – the heavenly trial and earthly operation – collapse in on each other. As Peter’s trial reaches its climax June, who had been watching every moment of the operation, is brought in front of the heavenly judge and jury who stand at the foot of that great moving stairway which has broken through into our reality, rooted in the operating theatre.

There, in the face of questioning, June secures Peter’s life not by the force of her testimony but by offering to step onto that stairway in his place. This decisive sacrifice breaks down the division between heaven and earth, and Peter is reprieved to live again on earth with June. And that victory is won not by rules, or argument, but by love.

As we wait and watch for the coming promise we do not wait and watch for an idea or a rule; we wait and watch for the gift of love which draws the great promise of heaven into our reality. We wait for that promise of love which shows how we might be transformed by God’s love to live without those limitations of grief or fear or regret which bind our lives today.

Hell: Isaiah 7:10-16

…the opposite of heaven …other people …the Metrocentre on the last weekend before Christmas?

We might not articulate what we mean by hell very often, but we all have a clear image of what we mean by that word; a place of seemingly eternal despair, a place with no redemption, no sign of hope.

In scripture hell – Sheol in Hebrew, Hades in Greek – acts as the bookend in the cosmological extremes of scripture: “as deep as Sheol or as high as heaven”, we hear in our reading from Isaiah. In the Hebrew scriptures Sheol is, on one level, the name for the place that lies beyond life, the dwelling place of the dead. It was to Sheol that Jacob says he will travel when he believes his son Joseph to be dead. However, it also carries with it an ethical dimension. Sheol becomes a place of punishment, where the godless are threatened with eternal misery, and some flaming fires to boot. This is of course much closer to our popular image of Hell with the ever circling descent to the deeper and more punishing levels of hell.

Dante, in his Inferno, recounts the journey through the nine circles of hell passing gluttons, heretics, blasphemers before Cain and Judas and the other great traitors of history open the door leading to Lucifer, the arch betrayer at the centre of hell. This is a powerfully poetic and arresting image of hell as the ultimate religious torture chamber. It is a place of suffering, the land of eternal death. The problem with this image of hell is that it stands on a contradiction. This place of eternal death is a place where the damned experience this death eternally. This death of deaths is in fact a place where people are supposed to live through this torment of eternal death.

However, if we return to the pages of scripture we find a different account of hell. As we come to this final Sunday in Advent and the final of the Four Last Things it is important that we do not get stuck on this poetic caricature of hell, but instead reflect on what the idea of hell means in our own journey of faith.

Martin Luther, the greatest of the reformers, saw hell not as some place beyond, but as part of the experience of God through the person of Jesus Christ. Instead of being seduced by caricatures of hell Luther encourages to look for hell in the experience of Jesus. In particular Luther draws us to the final days and hours of Jesus’ life where we hear of his descent into hell. Luther saw this descent not as a sojourn into Dante’s underworld, but as part of Jesus’ journey from the Garden of Gethsemane to Golgotha. In the experience of Jesus, we find this descent into hell was the experience of God-forsakenness: “My God, my god why have your forsaken me?” Jesus cries out from the cross. This hell is defined not by fire and sulphur; this hell is a place seemingly beyond the reach of God’s grace. Hell, is not the caricature of a bygone age or the one of the compass points of ancient cosmology. God-forsakenness is a universal experience, it is a contemporary experience. Hell, is a waste land we know and see all around us.

In 1922 T.S. Eliot took the literary world by storm in his series of poems known as The Waste Land. These complex poems hit the zeitgeist of European society still reeling from the destruction of the Great War. The landscapes of these poems are full of barren and polluted images, of the folly of war and decadence of the time, they are haunted by the lost youth of war. This waste land is truly a God-forsaken place.

In the first poem¸ The Burial of the Dead, a latter day Dante walks the streets of London seeing death all around him:

I was neither

Living nor dead, and I knew nothing,

Looking into the heart of light, the silence.

In the third poem, The Fire Sermon, Eliot draws allusions with St Augustine’s spiritual torments as a student in Carthage. But perhaps most powerfully is the image that opens the final, and finest poem in The Waste Land: What the Thunder said. Here Eliot takes us to the heart of that place of God-forsakeness. Drawing explicitly on Jesus’s final days Eliot moves through those moments of God-forsakenness, that hell that Jesus encountered: his betrayal and arrest in the garden, the agony of Golgotha, the destruction of the temple.

After the torchlight red on sweaty faces

After the frosty silence in the gardens

After the agony in stony places

The shouting and the crying

Prison and palace and reverberation

Of thunder of spring over distant mountains

He who was living is now dead

We who were living are now dying

Through The Waste Land Eliot holds a mirror up to the spiritual emptiness a God-forsaken world.

The extraordinary thing about The Waste Land is not its insight into the years after the First World War. The extraordinary thing about this poem is that it speaks so deeply of our experience today. It speaks of a world which too often seems forgotten by God, if there is a God at all: whether in the unfairness of life; or the meaningless consumption of the season; or the streets of Aleppo. Eliot’s words reminds us that for so many it feels that God has forsaken them.

That is hell.

In this barren landscape, in this waste land, it would be easy to think that there is no way out. But in Advent God shows us something different.

In Isaiah we hear God’s promise to a God-forsaken world in one decisive word, in one decisive promise. And that promise is Emmanuel – God with us.

It is worth us focusing on this word a little. In the promise of Emmanuel God is not saying “Don't worry, I'll swoop down from the clouds and sort this all out”, nor is God washing his hands of the whole sorry mess. Rather God is saying that he will come to be with us in the messiness and brokenness of our world. In a world of missed opportunities and political fudges, of human weakness and faithlessness, in world seemingly forsaken by God, God says Emmanuel: I will be with you.

In this passage from Isaiah we hear this deep decisive promise in the context of the slow collapse of the nation of Israel. Their leaders had lost faith in God, their end and exile seemed inevitable. And into this seemingly God-forsaken landscape God makes a promise: I will be with you.

As if we had not heard this promise clearly enough in Isaiah, we find it repeated and amplified a thousand-fold in our Gospel reading. That in this child to be born amongst the whole God-forsaken mess of our lives and world is truly Emmanuel, God-with-us.

And this is not a promise for thousands of years ago, but a promise for now. As we look at the waste land of our contemporary world, as we hear stories on the news, as we encounter the spiritual emptiness of a shopping centre the weekend before Christmas, as we reflect on our broken lives and broken relationships, we yearn for the fulfilment of that deep promise, for God to be with us.

We live in a world that for many feels forsaken by God. Whether we call it hell or not, it is a barren landscape of God-forsakenness. But in Advent we know this to be different. In Advent we hear again the ageless promise that this is not the case. We hear the deep promise of Emmanuel, God with us.

As we complete our journey through the Four Last Things we find that God answers our fears with that ancient promise, Emmanuel. In the places of death that surround us, even if we cannot see it, God is with us. When we stand in those places of judgement, we come to know that God is with us. In those glimpses and promises of heaven breaking in all around us we find again and again that God is with us.

And in a world and a time that for so many seems forsaken by God we are charged again to hold and proclaim to a forgetful world God’s deep promise: that in the heart of this barren waste land a child will be born, and his name will be Emmanuel.