Love is most nearly itself

When here and now cease to matter.

Old men ought to be explorers

Here or there does not matter

We must be still and still moving

Into another intensity

For a further union, a deeper communion

Through the dark cold and the empty desolation,

The wave cry, the wind cry, the vast waters

Of the petrel and the porpoise. In my end is my beginning.

From “Four Quartets: East Coker” by T.S. Eliot.

At the end of the nineteenth-century the German philosopher Friederich Nietzsche wrote about something we all recognise, a cow grazing in a field.

“Consider the cattle, grazing as they pass you by”, he said:

“They do not know what is meant by yesterday or today, they leap about, eat, rest, digest, leap about again, and so from morn till night and from day to day, fettered to the moment and its pleasure or displeasure, and thus neither melancholy nor bored. [...] A human being may well ask an animal: 'Why do you not speak to me of your happiness but only stand and gaze at me?' The animal would like to answer, and say, 'The reason is I always forget what I was going to say' - but then he forgot this answer too, and stayed silent.”

Nietzsche’s whimsical thoughts press in on something very profound for us all. When we think of our lives, when we examine our well-being, it is very often not the present moment that worries us. What gives us concern is the past and the future pressing in on our present moment.

“Why did I do that?”

“I wish that hadn’t happened?”

“Will that go OK?”

“How will I cope?”

To be human is to, a certain extent, to live in this historical frame edged by the past and the future. And when we are feeling oppressed by that frame we naturally look jealously at the cattle, ruminating in the moment, and we think that they seem to have the right answer.

That is why, if you go to any bookshop today, you will find armfuls of books encouraging us to release ourselves from the cage of a past we cannot change and a future we cannot control. Books on ‘Mindfulness’ teach us to savour and enjoy the present moment for what it is. The Scandinavian lifestyle craze of Hygge encourages us to slow down, to enjoy the simple things, and recognise the richness of now (mostly it appears by wearing thick socks and drinking hot chocolate). All this draws implicitly or explicitly on centuries of spiritual wisdom from the east and west which encourages us to live in the richness of our present experience, and through that to be released from the human prisons of the past and the future.

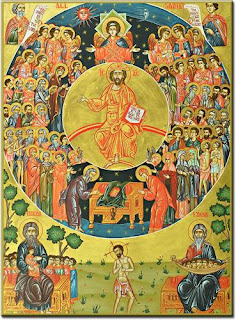

In light of this spiritual tradition the coming weeks in the Church’s year provide a great challenge. For a time we look back. In All Saintstide we look back to the saints of the Church. On All Souls’ Day we remember those we love by see no longer. On Remembrance Sunday we look back again to the violence and destruction of war.

And we also look forward. This is ‘Kingdom Season’ when the Church looks to the final consummation of God’s love at the end of time. With the feast of Christ the King at the end of the month we look to the future promise of the victory of God’s kingdom in all things.

This is a period in the Church year when we are held constantly by our past and our futures. We cannot escape it, but are we entrapped by this? Well the answer is no.

The reason we are not entrapped by these multiple pasts and futures is because through these weeks we focus again and again on one deep truth of our faith, the great Christian virtue of hope. Hope is too often seen as a woolly idea, a way of parking a problem in the long-grass: “I hope it will be alright” “We live in hope”. But Christian hope is something more profound and transformative than this. The German Theologian Jürgen Moltmann puts it this way:

“Christian hope is the power of the resurrection from life’s failures and defeats. It is the power of life’s rebirth out of the shadows of death. It is the power for the new beginning at the point where guilt has made life impossible.”

Christian faith is built on hope, Moltmanm reminds us, because our faith is built on the Cross and Resurrection. The Cross, illuminated by the Resurrection, shows that there is nothing – not even the cruellest and most demeaning of torture and death – which does not have a future in God.

The unique call of Christianity is that instead of hiding from the problems of our past or pushing the concerns of our future into the long grass it embraces them. Through our faith we have the sure and certain hope in the future, because we know that God’s love redeems and makes new all our past failures and mistakes.

We find this promise of hope clearly in our Gospel reading:

“Blessed are you who are poor, for yours is the kingdom of God.

Blessed are you who are hungry now, for you will be filled.

Blessed are you who weep now, for you will laugh.”

Rather than turn away from our pasts and futures Jesus offers us hope not despite of our past experience, but by blessing it and redeeming it.

Blessed is that part of your life you would wish to change;

Blessed is that relationship that failed;

Blessed is that thing you wish you hadn’t done

All these pasts are blessed because through God’s love and power they are transformed into the future that God promises to us all. At All Saintstide, and in fact through all of Kingdom season, we can look back and find ourselves ensnared by the past.

“How can I live up to the saints of the past?”

“How can we atone for the failures of the past?”

“Can I change that thing which seems to dominate so much of how I live now?”

In Kingdom Season we are encouraged not to hide from our pasts or ignore the possibility of our future. Through this season God invites us to seek God’s presence in all these past experiences so that we might know again the transforming power of Christian hope and know an even more glorious future

No comments:

Post a Comment